Ideas about good and bad painting are often uncertain because of a tendency to confuse representation with copying. While people praise and admire lifelike portraiture and landscape painting, they also suppose that artists should not merely copy what they see but add an element of personal ‘interpretation’. It is in this ‘interpretation’ that many people think the art lies and which raises it above simple copying. This is partly why they often wonder whether photography, which merely reproduces what is ‘there’ by causal means, can really be an art.

Yet whether photography is an art or not, it does not produce copies of the appearance of things. We never see in sepia or monochrome. When I look at a black and white photograph of a group of people one of whom has red hair, that person is represented in the picture, but not by a copy of her appearance. Even in a full-colour photograph, the redness of her hair can be enhanced by filter, exposure or lighting. Besides, every photograph has an angle from which it is taken. Since there is no neutral position that we can think of as the ‘true’ angle from which a person or an object has to be seen, the angle is the choice of the photographer. ‘Copying’ suggests passivity, but perfect passivity in photography is impossible. It is this fact and other similar facts upon which the art of the photographer is built.

The same is true of painting. We are inclined to think of representation as copying partly because the dominant convention in painting has long been to represent via strict resemblance. But this need not be so. Figures in ancient Egyptian art often appear peculiar and somewhat primitive to us, as though the artists were incapable of better. Part of the reason for this, however, is a different convention in representation. Ancient Egyptian art operated with the principle that each part of the human anatomy should be represented from the angle at which it is best seen. Thus, while the face was depicted in profile, the torso was depicted from the front, and legs and feet from the side. Taken as a whole the end result was a body unlike any that has ever been seen. But it would be a mistake to conclude that there was some failure of representation. There was merely a different convention of representation. Ours may seem to us more ‘natural’, as perhaps it is, but its naturalness should not deceive us into thinking that it is more representational.

Foreshortening, perspective, the use of light and shade, which contribute so significantly to representation in Western art, were all important discoveries that greatly increased the power of the painter. But the power they give to the painter is not to reproduce what is ‘there’ but to create a convincing impression that we are seeing the thing represented. The consequence is that even the most lifelike representations cannot be thought of as mere copies. Their creators follow conventions determining how things are to be represented and employ techniques which oblige us to look at things in certain ways. John Constable (1776–1837), that most ‘natural’ of painters, The Haywain is one of the best-known and best-loved pictures in existence, uses blues and greens that are never actually found in sky or foliage. In Gimcrack, George Stubbs (1724–1806) represents the speed of a racing horse very effectively, but movie stills reveal that horses do not actually gallop that way. (All the paintings referred to in this chapter can be found in E. H. Gombrich’s The Story of Art (1995). Any depiction of nature that tries just to copy must fail, partly because every ‘copy’ of nature must involve seeing selectively, and partly because the work must reflect the representational resources available to the painter.

The divorce between representation and copying is complete when we turn to a popular area of visual art – cartoons. No mouse ever looked like Mickey Mouse and no ancient Gaul ever looked like Asterix, yet it is obvious even to small children what they are. Many famous woodcuts, drawings and engravings could be cited to sustain the same point. It is simply a mistake to think of representation in the visual arts as a simple attempt to ‘copy’ what is ‘seen’.

Representation and artistic value

‘Resembling’, ‘copying’ and ‘representing’ are easily confused, but they are quite different. Cartoons can represent without resembling, and pictures can resemble the things they represent without being copies of them. Under the influence of naive representationalism people sometimes complain that the faces and figures in so-called ‘modern’ art do not look anything like the real thing. This is probably not a complaint peculiar to the modern period. It seems likely that those brought up on the highly realistic pictures of Dürer (1471–1528) and Holbein (1497/8–1543) thought something of the same about the rather more extravagant paintings by El Greco (1541– 1614). But the important point is that if representation and resemblance are different, the visual arts can abandon resemblance without ceasing to representational. Might they then go further, and abandon representation without ceasing to be art?

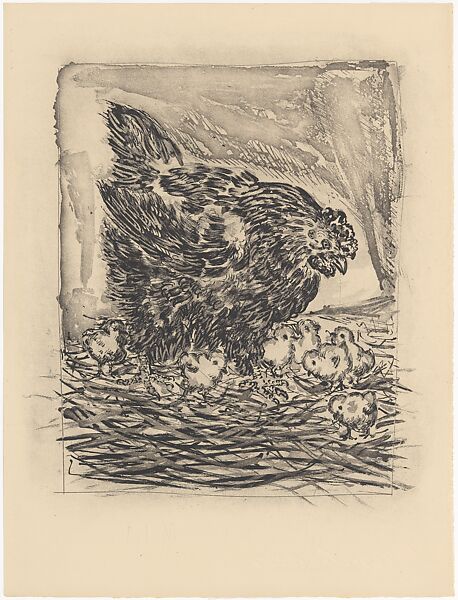

One reason for thinking so is the fact that some outstanding artists whose skill at representation is unquestionable have abandoned strictly representational painting. In The Story of Art Gombrich invites us to compare Picasso’s A Hen with Chickens with his slightly earlier picture A Cockerel. The first of these is a charming illustration for Buffon’s Natural History, the second a rather grotesque caricature. Gombrich makes the point that the first of these pictures amply demonstrates Picasso’s ability to make lifelike representations. Consequently, when we note that the second drawing looks ‘nothing like’ a cockerel, instead of dismissing it we should ask what Picasso is trying to do with it. According to Gombrich, ‘Picasso was not content with giving a mere rendering of the bird’s appearance. He wanted to bring out its aggressiveness, its cheek and its stupidity’ (Gombrich 1987: 9).

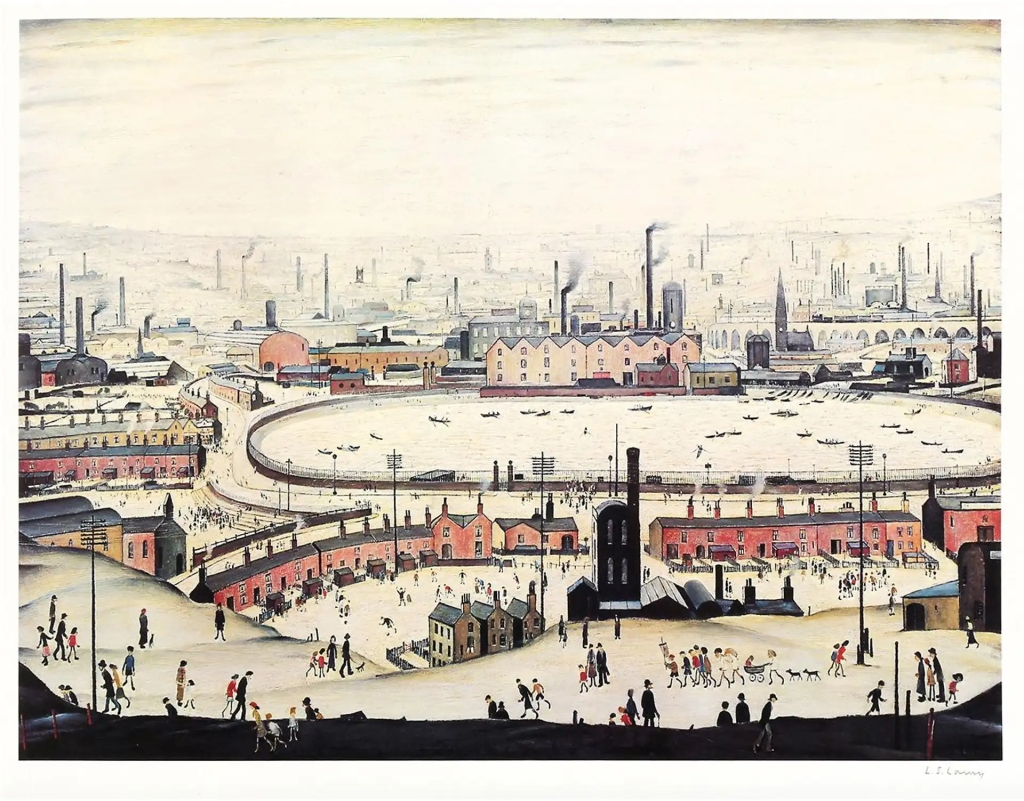

L. S. Lowry (1887–1976) is another artist illustrative of the same point. In his most famous pictures people are generally drawn with a childish simplicity, ‘stick’ figures in fact, but his early drawings of male nudes show that this manner of depiction was a matter of choice, and we will only appreciate the pictures properly if we look into the reason for that choice.

Gombrich’s interpretation of the Picasso cartoon brings out an important distinction that representationalism tends to overlook. There is a difference between representing something and giving a rendering of something’s appearance. Those who favour representational art usually mean to favour painting that gives a good rendering of the appearance of things. As we have seen, ‘giving a good rendering’ is not a matter of ‘copying’ the appearance of things but creating something that resembles and thereby gives the viewer a convincing impression of having seen the object. Now what the example of Picasso’s cockerel shows is that the creation of a resemblance is only one purpose for representation. The cartoon does not look like a bird we might see, but it is still representational. What it represents is not the bird’s appearance, but its character. This shows that representation can serve purposes other than creating a resemblance, and in turn this opens up the possibility that these other purposes can be served by means other than representation.

Consider some further examples of representation. Almost all the painting from the European Middle Ages is religious in inspiration and purpose. The aim of much of it was to provide the illiterate faithful with instruction in Bible stories, Christian doctrine and the history of the Church, especially the history of its saints and martyrs. It did not aim at mere instruction, however, since it sought also to be inspirational, to prompt in those who looked at it an attitude of mind that would be receptive of divine grace. One interesting example of this is Dürer’s engraving The Nativity (Dürer is a particularly good choice here because his pictures give such obviously excellent ‘renderings of the appearance of things’). The engraving shows a dilapidated farmyard in which Joseph, depicted as an elderly peasant, is drawing water at the well, while in the front left-hand corner Mary bends over the infant Jesus. Much less prominently portrayed (looking through a rear doorway in fact) is a kneeling shepherd, accompanied by ox and ass. In the very distant sky there is a single angel.

Albrecht Dürer German 1504

The difference in scale of these traditional nativity figures, relative to the house and farm buildings, is striking. But it is also a little misleading; the picture is not any the less a nativity scene than those in which shepherds and angels are more prominent. What Dürer has done, by a magnificently detailed representation of a common Northern European farmhouse, is to convey very immediately the compel- ling atmosphere of Holy Night with the purpose, we may suppose, of inducing a deeper sense of the mystery of the incarnation in the sort of people for whom the picture was intended.

Compare Dürer’s engraving with No. 1 by Jackson Pollock (1912–56). This painting is a result of Pollock’s celebrated ‘technique’, later known as ‘action painting’, in which the canvas is placed on the floor and commercial enamels and metallic paints are dripped and splashed on it spontaneously. The outcome is an interesting and unusual pattern which the advocates of action painting thought revealed something of the artist’s unconscious. But whether it does or not, the painting itself does not resemble anything.

At first sight, these two paintings could hardly be more different. Pollock’s was intentionally the product of spontaneity and made with some speed, Dürer’s the result of hours of painstaking work. Dürer’s is representational to an unusually high degree, Pollock’s wholly non-representational. Yet despite these striking differences, it is not implausible to say that both works share something of the same purpose. Pollock’s No. 1 is an example of ‘abstract expressionism’, and much of the painting that falls under this label was influenced by Eastern mysticism. Both the spontaneity of production and the random patterns it brings about were thought valuable because they shake ordered preconceptions. We are forced to see visual chaos rather than visual pattern and thus to see the uncertain, even unreal, nature of the world of appearance. Using the visual to create impressions of unreality is similar to the way in which some versions of Buddhism try to shake our preconceptions as a means of spiritual enlightenment. The paintings of abstract expressionism might be thought of as visual equivalents of Zen koans, the questions which the novice is made to contemplate, such as ‘What is the sound of one hand clapping?’ Interpreted in this way, both Dürer’s and Pollock’s paintings, despite their striking differences, share the same purpose – to make people aware of spiritual realities behind everyday experience. It is not crucially important here whether the spiritual purpose so described fits either case. These two pictures illustrate the point that, in intention at any rate, representational and non-representational styles of painting, despite their radical differences, are both means that can be employed to the same artistic purpose.

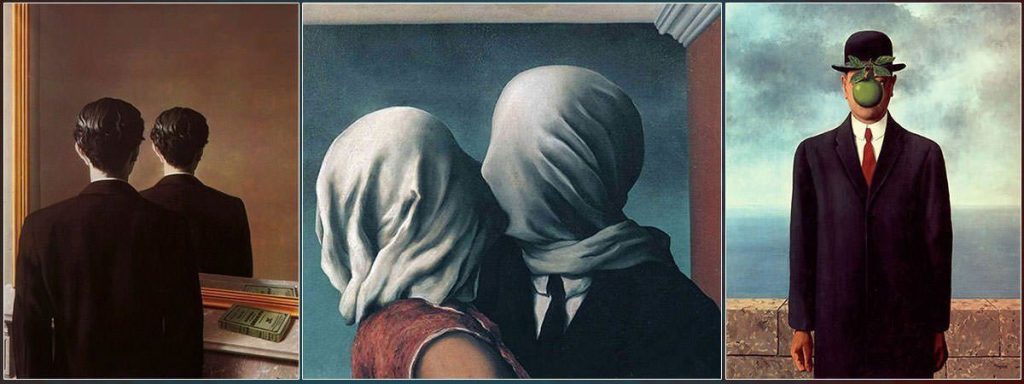

What this shows is that we should not think of representation as the sole or even chief end of visual art, but only as one, admittedly very prominent, means. To see this is to reject representation as the criterion by which visual art is to be judged, since a means is only as valuable as the end it serves. It remains the case, of course, that representation is the stock in trade of visual artists, and nothing in the foregoing argument involves denying this. Even the Surrealists, a school of which Salvador Dali (1904–89) is perhaps the best-known member, who rejected the idea of ‘renderings of the appearance of things’ still made extensive use of representation. One of its greatest exponents, Rene Magritte (1898–1967), is a brilliant representational artist, but the things he represents are fantasies that could not possibly be how actual things appear.

We should infer from this, not that most painting is visual representation, but that representation is a highly valuable technique in visual art. Importantly, it is not the only one; there are other techniques to be explored. But to understand the value of visual art, we must go beyond both representation and these other techniques, and seek the ultimate purpose they serve. This brings us back to our central question. What is the most valuable end that art can serve? Preceding chapters concluded that neither pleasure, nor beauty nor the expression of emotion can adequately fill this role. The answer aesthetic cognitivism gives is, ‘Enriching human understanding.’ Can painting do this and, if so, how?

[taken from Philosophy of the Arts; An Introduction to Aesthetics by Gordon Graham 1997]